October 9, 2021

Today we begin a new Saturday series about a time when there was contract negotiations, workman’s compensation, and representative democracy long before any national government considered such things, and all of it under the Skull and Crossbones: The Pirate Republic.

Depending on who is counting, the Golden Age of Piracy either lasted 10 years, from 1715 to 1725, or 20, beginning in 1705, or 35, beginning in 1690 (I’m going with this third date). It was conducted 20 to 30 pirate commodores and a few thousand crewmen. They ran their ships democratically, electing and deposing their captains by popular vote, sharing plunder equally, and making important decisions in an open council – all in sharp contrast to the dictatorial regimes in place aboard other ships.

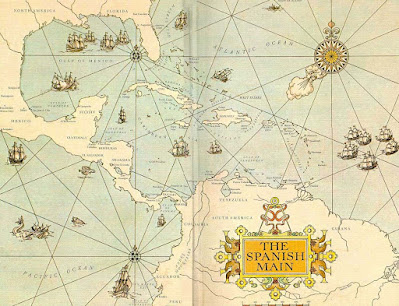

At their zenith the pirate gangs of the Bahamas severed Britain, France, and Spain from their New World empires, cutting off trade routes, stifling the supply of slaves, and disrupting the flow of information between the continents.

In the process, some accumulated staggering fortunes, with which they bought the loyalty of merchants, plantation owners, even the colonial governors themselves.

The Golden Age pirates had a role model in Henry Avery, a “pirate king” who led his fellow crewmen from oppression between the decks to a life of unimaginable luxury in a pirate kingdom of their own.

Avery’s adventures inspired plays and novels, historians and newspaper writers, and, ultimately, the Golden Age pirates themselves. This tale properly starts with Henry Avery, and the arrival of a mysterious ship in Nassau three centuries ago.

The sloop arrived in Nassau’s harbor the afternoon of April Fool’s Day 1696. Captain Henry Bridgeman and several strangers went to the home of Governor Nicholas Trott.

Nicholas Trott’s colony was in trouble. England had been at war with France for eight years, disrupting the Bahamas’ trade and supply lines. The French were headed for Nassau with three warships and 320 men. The residents had Fort Nassau, but with many settlers fleeing for the better protection of Jamaica, South Carolina, and Bermuda, it almost impossible to keep the structure manned. There were no more than seventy men left in town, including the elderly and disabled. If the French attacked, there was little hope.

They explained that he and his colleagues had recently arrived in the Bahamas aboard the Fancy, a private warship, and sought Trott’s permission to come into Nassau’s harbor. The Fancy had run low on provisions and its crew was in need of shore leave. The strangers offered a bribe worth some £860 (one pound Sterling in the late 17th century was equal to approximately $100 today). The governor’s annual salary was £300. To top it off, the crew would also give him the Fancy herself, once they had unloaded and disposed of their cargo.

Governor Trott called an emergency meeting of the governing council, neglecting to mention the bribes. He appealed to their security. The Fancy might deter a French attack. The members of the council concurred. Not long thereafter, a great ship rounded Hog Island. The promised loot was there: a fortune in silver pieces of eight and golden coins minted.

And with that, England’s most wanted man bought off the law and secured one of His Majesty’s own governors as his protector. Captain Bridgeman was in reality Henry Avery (sometimes spelled Every), the most successful pirate of his generation.

In the spring of 1693, Avery heard that a squadron of merchant ships was being hired by Spain, to plunder French ships and plantations. Their contract promised a guaranteed monthly wage at fair rates, with one month’s pay advanced before the ships even left England. There would also be a share of the plunder. Avery was hired as first mate aboard the expedition’s flagship.

When they arrived in northern Spain almost five months late, they found that the privateering documents were not there. A month later, the men’s promised semiannual salary payment had not yet been made. They petitioned the owner of the squadron who, in response, had several petitioners put in irons and lock them in the ships’ brigs.

Henry Avery and some of his fellow sailors seized the lead ship in the convoy and headed to the open Atlantic.

He proposed that they sail for the Indian Ocean, where they would go after the richly laden merchantmen of the Orient and keep the plunder for themselves.

Thirteen months after the mutiny in Spain, Avery’s gang had captured at nine vessels. But they only very small quantities of gold and silver. They needed a bigger prize. They learned that a fleet of 25 ships would be sailing from the Red Sea on its way to India. The convoy’s treasure ships – property of the Grand Mogul of India – were the most valuable vessels to sail the Indian Ocean.

Avery and five other English privateers agreed to attack the treasure fleet and share the plunder. They missed the first 24, but did capture the very last vessel netting £50,000 in gold and silver, and then chased the rest of the fleet.

Two days later, they spotted the Grand Mogul’s personal vessel. The Mogul fired, but the cannon exploded, blowing the gun crew to bits. The Fancy returned fire, collapsed the mainmast, and the pirates swarmed on board.

The pirates took £150,000 of treasure. Most of the crew received an individual share of £1,000, the equivalent of 20 years’ wages aboard a merchant ship.

Back in Nassau, a few men stayed and married local women. The remaining pirates split into three parties. The first group sailed quietly for England. The second went to Charleston. The third group consisted of Avery and 20 others, who bought a sloop, loaded their possessions and treasure on board and made ready to depart. They sailed for Ireland.

The first group vanished in England. The ones who sailed to the colonies disappeared. Avery’s group landing in County Donegal where he parted ways with his men, saying he was bound for his native Devonshire. Only one person accompanied the pirate: his first mate’s wife. Avery was never heard from again.

|

| Avery selling diamonds to raise cash for his disappearance. |

Rumors of Avery’s exploits circulated the English-speaking world for decades. He was proclaimed the King of the Pirates, and was rumored to have established his own pirate domain in Madagascar. Avery would become the role model for the men who dominated The Golden Age of Piracy.

👉 Today’s close “Exposed to a Higher Standard,” is by Max Lucado.

Most of my life I’ve been a closet slob. I was slow to see the logic of neatness. Why make up a bed if you are going to sleep in it again tonight? Does it make sense to wash dishes after only one meal? Isn’t it easier to leave your clothes on the floor at the foot of the bed so they’ll be there when you get up and put them on?

Then I got married.

I enrolled in a twelve-step program for slobs. (“My name is Max, I hate to vacuum.”) A physical therapist helped me rediscover the muscles used for hanging shirts and placing toilet paper on the holder. My nose was reintroduced to the fragrance of Pine Sol.

Then came the moment of truth. Denalyn went out of town for a week. Initially I reverted to the old man. I figured I’d be a slob for six days and clean on the seventh. But something strange happened, a curious discomfort. I couldn’t relax with dirty dishes in the sink.

What had happened to me?

Simple. I’d been exposed to a higher standard.

Isn’t that what has happened with us?

Before Christ our lives were out of control, sloppy, and indulgent. We didn’t even know we were slobs until we met him.

Suddenly we find ourselves wanting to do good. Go back to the old mess? Are you kidding?

-30-

No comments:

Post a Comment