March 20, 2021

At 7:33 a.m. on June 18, 1983, the space shuttle Challenger lifted off from pad 39-A at the Shuttle Launch Complex. STS-7 was the seventh trip for the nation’s two-year-old space shuttle system. The shuttle itself was still a pioneering program, but this mission was historic: the first flight of an American woman into space.

Sally K. Ride immediately connected to Americans everywhere by radioing: “Have you ever been to Disneyland? This is definitely an E ticket!”

Fifty-two American women have flown into space, out of a total of 65 women from all nations (Soviet Union – 2, United Kingdom – 1, Canada –2, Japan –2, Russia – 2, France – 1, Iran – 1, South Korea – 1, China – 2, Italy – 1, Sweden – 1).

Shannon Lucid set an endurance record on the space station, MIR.

Eileen Collins became the first female shuttle pilot in 1995. Five years later, she slid over to the vaunted left-hand seat and became the shuttle’s first female commander.

Four women have given their lives for the program – Judy Resnik and Christa McAuliffe on Challenger in 1986, and Kalpana Chawla and Laurel Clark on Columbia in 2003.

Five decades ago, women were too weak, too emotional, too, well, womanly, to participate. And, of course, they simply weren’t qualified.

In June, 1957, Geraldyn M. Cobb’s goal was to the break the world altitude record for lightweight aircraft of 27,000 feet. Jerrie Cobb was hoping for 30,000.

She knew that at several miles up breathing became difficult, vision was impaired, and a pilot could slip into unconsciousness. She also knew that – as absurd as it seemed – she had to worry about her appearance as well. Unspoken social customs for women pilots dictated that she wear a dress and high heels under her protective clothing.

At 30,330 feet, the Aero Commander started to shudder, but she had clinched the world record, surpassing the one set by a male Russian pilot flying a Soviet Yak II. A mechanical problem was later discovered on the measuring device, and she had to repeat the flight. This time she flew again to 37,010 feet.

Dr. W. Randolph Lovelace II, chairman of NASA’s Life Sciences Committee, and Brigadier General Donald Flickinger of the Air Force helped design the medical testing procedures for the astronaut candidates. Lovelace and Flickinger were interested in testing women for potential spaceflight.

After a chance meeting with Dr. Lovelace and General Flickinger just months after the press conference introducing the Mercury 7 astronauts, Jerrie Cobb became their test subject. When learned about Cobb’s tests they dubbed her “America’s first woman astronaut.”

Flickinger approached NASA with the idea of testing women for their viability as astronauts. NASA was not interested. The space agency believed women were physically incapable of handling the demands of space. Flickinger and Lovelace, decided to test a woman as part of their own independent experiment. If their results proved that a woman scored well on the same tests that the Project Mercury astronauts underwent, Flickinger would again approach NASA with the data.

Interestingly, in spite of the extensive medical tests performed on the Mercury 7, Alan Shepard and Deke Slayton were grounded for medical conditions – Shepard with an inner ear disorder and Slayton with a heart murmur.

Alan Shepard finally returned to flight status after surgery corrected the ear problem, and flew as commander of Apollo 14 (with Ed Mitchell & Stuart Roosma).

Deke Slayton missed Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo, as well as Sky Lab, but he was granted medical clearance in 1972 and flew as the docking pilot on Apollo-Soyuz.

|

| Deke Slayton, Tom Stafford, Vance Brand, Alexi Leonov, Valeri Kubasov. |

In February 1960, Jerrie Cobb began astronaut tests. Carpenter, Cooper, Glenn, Grissom, Slayton, Shepard, Schirra, and 24 other male candidates had been competing against one another for a chance to be selected as one of the nation’s first astronauts. Had Shepard or Glenn not succeeded, other men would have been selected in their place. If Jerrie Cobb did not succeed, however, neither she nor any other woman would likely get another shot.

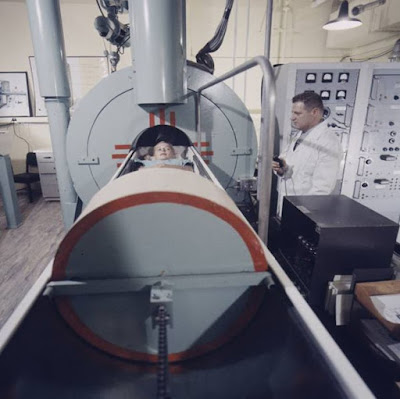

For six days Cobb battled tilt tables, electrical stimulation to the nerves, three feet of rubber hose slithered down her throat, exhausting physical endurance exercises, frozen ears, frozen hands, frozen feet, brainwave measurements, radiation counts, and the nightly dose of humility – barium enemas. In all, doctors scheduled a total of seventy-five tests to measure the range of her body’s capability.

Dr. Lovelace compared her scores with the Project Mercury astronauts, and initial indicators suggested that she had done very well. But he knew that NASA would view Jerrie Cobb’s exceptional test scores as a fluke and not representative of women pilots in general. He began compiling a secret list of women pilots who had racked up more than a 1,000 hours in the air, not an easy task in the 1960s, since women were not allowed to fly for the military and were not being hired by airlines.

Next week, I’ll introduce you to 12 women pilots who wanted to carry on the story, completing the Mercury 13.

👉 God So Loved!

On June 7, 1885, 30 years after he began preaching, Charles Spurgeon delivered a message entitled, “Immeasurable Love.” His text was John 3:16, one of the Lenten texts for this week – “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.”

As he began Spurgeon said, “I was very greatly surprised the other day, in looking over the list of texts from which I have preached, to find that I have no record of ever having spoken from this one verse. This is all the more singular, because I can truly say that it might be put in the forefront of all my volumes of discourses as the sole topic of my life’s ministry. It has been my one and only business to set forth the love of God to men in Christ Jesus.”

“God so loved the world.” It is astonishing to think of the wonderful love of God set on this world. What was there in the world that God should love it? We are only 6 chapters into the Bible until we read, “The [population of the] earth was corrupt [absolutely depraved—spiritually and morally putrid] in God’s sight, and the land was filled with violence [desecration, infringement, outrage, assault, and lust for power]. God looked on the earth and saw how debased and degenerate it was, for all humanity had corrupted their way on the earth and lost their true direction” (Genesis 6:11-12 AMP).

But “God loved the world,” says John, “so” loved it, it that he gave his Son, His only Son, to redeem the world from perishing, and to gather out of it a people to His praise.

Such a love requires a response.

-30-

No comments:

Post a Comment