December 5, 2020

Conclusion

The Attorney and the Vienna Belle

Maria was in her eighties. She and Fritz had reinvented their lives in America, raising four children in a modest West Side Los Angeles ranch house. Fritz died in 1994.

In February 1998 she got a phone call from an old friend in Vienna. An article had appeared suggesting that the Bloch-Bauer Klimt collection had been stolen by the Austrians. A few weeks later, Maria asked her sister, “Should we try to get the Klimts back?”“That,” Luise replied, “would require an excellent lawyer.”

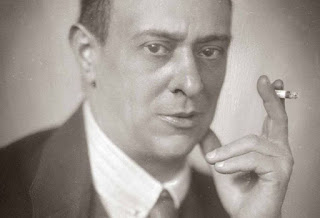

Randol Schoenberg was handling securities litigation at Fried Frank Harris Shriver & Jacobson when Maria called. He had strong ties to Vienna.

His grandparents, Gertrude and Erich Zeisl, fled Vienna, escaped to Paris, and then to New York City.

Randol’s paternal grandfather, Arnold Schoenberg, was a brilliant Austrian composer who fled the rise of Hitler and was on the Reich’s list of “degenerate artists.”

Randol never forgot that he was alive because his grandparents had fled. He believed there were still battles left to fight. He found it outrageous that Austria had largely evaded the return of stolen Jewish property. He offered to take Maria’s case on a contingency basis.

Meanwhile Hubertus Czernin was developing a series of books on the history of Nazi art theft in Vienna.

As far as he was concerned, Austria had failed to compensate its murdered and wronged Jewish citizens. Lost lives could never be recovered. But paintings could be returned. Hubertus set out to combat the historical amnesia.

In Los Angeles, Randol wasn’t getting far making overtures to Viennese officials. Someone pointed Randol toward Hubertus Czernin. Encouraged by the contact, in March 1999, Maria flew to Vienna. She climbed the grand staircase at the Belvedere Palace until she came face-to-face with Klimt’s golden Adele in the grand salon. She asked someone to photograph her in front of Adele. A young guard warned that photos were prohibited. “This is my aunt!” Maria retorted angrily. “This painting belongs to my family.”

The Belvedere “is not the legal owner of these paintings,” Maria wrote to the Beirat, the Vienna Advisory Council on art restitution. “We are keenly aware of the Gold Portrait’s importance as a national treasure. Once the Beirat decides to recognize our legal right to the paintings, we would then be in a position to work out a way ... that leaves the portrait in Vienna.”

Maria never got an answer to the letter, or any others she wrote to Austrian officials.

Randol appealed to the Austrian culture minister, Elisabeth Gehrer, offering to settle the case through arbitration in Austria. Her response: You can contest the decision in court, but you must pay $1.8 million as a deposit against court costs, based on a portion of the estimated value of the paintings. There was no possible way they could do that.

In August 2000, Randol and Maria filed suit in U.S. federal court in Los Angeles. In May 2001, Los Angeles federal judge Florence-Marie Cooper ruled Randol and Maria’s case could go forward in U.S. courts. Judge Cooper ruled that Austria was an inadequate forum for the claim because of its “unduly burdensome” court filing fees.

In December 2002, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Maria could sue in U.S. courts under an exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act for property stolen in violation of international law. The Austrians appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court case seemed a long shot. The George W. Bush administration filed a brief with the Supreme Court, supporting Austria’s position. Randol and Maria figured they had nothing to lose.

David Pike, a veteran Supreme Court reporter in his sixties, predicted in the Los Angeles Daily Journal that Randol would lose.

For the next three months, Randol checked the Supreme Court website. One morning, as he made breakfast for his kids, the phone rang. It was David Pike. This was a very bad omen. “Okay, give me the bad news,” Randol said. Pike paused. “You won,” he said.

The ruling allowed Maria’s lawsuit to proceed. Now Austria faced the daunting prospect of defending itself against a prominent Holocaust case in a U.S. court.

Randol told Maria he thought they should accept an Austrian offer to submit the case to binding arbitration with a panel of Austrian legal experts. Maria finally agreed.

Randol appeared before the Austrian arbitration panel in Vienna in September 2005 to present his case. Under the terms of the arbitration, Randol had chosen one of the arbitrators, a charismatic barrister, Andreas Noedl. Austria chose its own expert, Walter Rechberger, the dean of the University of Vienna Law School. Noedl and Rechberger elected the third panelist, Peter Rummel, a distinguished law professor.

Finally, on January 15, 2006, the three arbitrators made a decision. Unbelievably, Randol and Maria had won!

Adele’s Final Destiny

Lines stretched around the block at the Belvedere Palace as people crowded in for a last look at Adele. Posters of the gold portrait of Adele appeared overnight, staring out from bus stops and kiosks, with bold letters: “Ciao Adele.” Goodbye Adele.

Finally, Adele’s portrait and the other four Klimts were carefully crated. False itineraries were circulated by e-mail, to throw off would-be thieves. The five paintings left the Belvedere before dawn, to avoid protesters. They were loaded on an unmarked truck, and flown to Los Angeles.

In June 2008, Ron Lauder bought the gold portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer for his Neue Galerie. The price was a record $135 million. Gustav Klimt, once branded as a pornographer, was now the creator of the world’s most expensive painting.

After months of family bickering, the end of the saga would come at the Christie’s auction in New York as the four Klimt paintings were sold along with other object d’art.

Watch a video of The Auction.

One of the first items up was Picasso’s “Tomato Plant.” Bidders quickly eclipsed the presale estimate of up to $7 million. The painting sold for $13.4 million. This seemed to set the high-flying tone. A tiny sliver of hammered green metal on a wooden base was presented as La Jambe, or “The Leg,” by Alberto Giacometti. It had a presale estimate of up to $2.5 million. But the tiny leg went for $7.9 million.

Finally, the Klimts. “Birch Forest” was first and sold for $36 million. “Castle Chamber at Attersee” went for $28 million. “Apple Tree” sold for $29.5 million. The second portrait of Adele sold for $78.5 million.

In six minutes, the Klimts were sold. The gavel prices totaled $192.7 million. The proceeds, combined with the $135 million sale of the gold portrait, would be divided among Randol’s 40% contingency fee ($131 million) and Adele’s five surviving heirs.

In the end, many things led to the restitution of the Bloch-Bauer Klimts. There was the higher moral standard, demanded by the living victims of an unprecedented historic crime. In the days of Napoleon, war meant booty. It was accepted: to the victor went the spoils. Now people were disturbed by art taken by force and kept by deception.

“The Lady in Gold” was reborn. The portrait had been created, stolen, renamed, and consigned to a shadowy underworld. It had miraculously eluded the inferno of war. A man who had seen Adele and never forgotten her paid $135 million to buy her, legally, for the first time. Adele was now legend.

👉 First Saturday in Advent

Glory in the Wilderness

“They shall see the glory of the Lord, the majesty of our God” (Isaiah 35:2).

“The voice of one crying out in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight’” (Matthew 3:3).

Advent is the season when we await the coming of God’s glory, which has not yet come. Glory. Since the word is so odd, we may wonder exactly what it is that we wait for. We may even ask if we would know it if we received it.

The glory of Yahweh is not simply bland, ordinary, enthusiastic religion. The glory of God is not sung in a vacuum but in a context where much is at risk.

The context, according to this poem, is the wilderness and the desert. The wilderness is a place where the power for life is fragile and diminished. The inhabitants of the desert are those with weak hands and feeble knees and fearful hearts, those who have had their vitality crushed and their authority nullified and their will for life nearly defeated. This poem is a roll call of the marginalized, the blind, the deaf, the lame, the dumb, all the disabled. The wilderness is a place where the power for life is fragile and diminished.

It is Advent time in the wilderness. Shriveled up earth and crushed down humanity wait for the coming, in the wilderness. It is no wonder that John quotes Isaiah, “Prepare in the wilderness a special way.” It is no wonder that John, in anticipation of Jesus, says, “They shall all see the glory.” They shall all see God’s massiveness and power that transforms. The wonder and the oddness is that in the shadow of that great glory comes the protected, rescued, vulnerable, valued ones who travel for the first time in safety and in joy. There finally is shalom on earth, even in the desert. The choirs, however, never sing of shalom on earth, until they first celebrate the glory. The shalom of the desert follows from the glory of God.

In Advent, we know about the God who transforms, makes new, and begins again. No wonder creation and humanity, one at a time, all together, sing of the new world bursting with the abundant glory of God.

Too often we have become inured to the wilderness, O God, to the fragility and diminishment of life. But Advent is the season of your coming. May we celebrate your glory and sing of your shalom. Amen.

-30-

Wrongs like the theft of the Adele portrait when exposed must made right whenever possible. The money didn't matter. It was a matter of morality. "Thou shalt not steal" is a moral imperative that is recognized among the civilized nations of the world whether they agree or not.

ReplyDelete