April 8, 2022

Ralph Terry, Yankee Hurler Redeemed by One Pitch, Dies at 86

In 1960 he gave up the home run that secured a World Series victory for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Two years later he got the final out of the Series against the San Francisco Giants to win the World Series for the New York Yankees.

|

Ralph Terry was carried to the clubhouse by his teammates after he shut out the San Francisco Giants, 1-0, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco to win the 1962 World Series for the Yankees. |

By David Margolick

Ralph Terry, the Yankees pitcher who threw two of the most dramatic and decisive pitches in baseball history, each of them ending a World Series but with stunningly different outcomes, died at a long-term care facility in Larned, Kansas. He was 86.

The first of Terry’s celebrated pitches came on October 13, 1960, when, in the bottom of the ninth inning against the Pittsburgh Pirates, Bill Mazeroski sent it soaring over the ivy-covered left field fence at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, giving the Pirates a 10-9 win over the Yankees in the seventh game of the World Series.

“I should have curved him,” a despondent Terry said in the dressing room afterward. He had thrown Mazeroski a slider.

Terry’s second storied pitch, two years later against the San Francisco Giants in Candlestick Park, produced a wicked line drive off the bat of the slugger Willie McCovey that landed squarely in the mitt of the Yankees’ second baseman, Bobby Richardson, preserving a 1-0 New York victory in the decisive game and sparing Terry an ignoble spot in baseball history as a double World Series loser.

“Thank God,” he declared joyously afterward, adding, “It’s rarely in a man’s life that he gets a second chance.”

Terry spent all or part of eight seasons with the Yankees. He won 78 games for New York, including 23 in 1962. But it is his contrasting fates in two classic World Series games for which he is best remembered.

The 1960 Game 7 in Pittsburgh was a dramatic seesaw climax to an eccentric series. The Yankees had crushed the Pirates in every game they’d won and barely lost those they didn’t. In the rubber game, they’d come back from a 4-0 deficit to go ahead, 7-4, only to see Pittsburgh score five runs in the bottom of the eighth. Terry, who had started and lost the fourth game, came in to squelch that rally, retiring Pittsburgh’s third baseman, Don Hoak. The Yankees promptly tied the score in the top of the ninth.

|

Terry pitched the Yankees to the championship in Game 7 of the 1962 World Series; a marked contrast to the final game of the 1960 Series, in which he gave up the winning run. |

But something was wrong, and Terry knew it when he returned to the mound. As a parade of Yankee pitchers – Bob Turley, Bill Stafford, Bobby Shantz, Jim Coates – faltered earlier in the game, Terry had warmed up repeatedly, and he realized he’d left his best stuff in the bullpen. The game remains the only one in World Series history without a single strikeout.

The curve that retired Hoak had actually hung. “He should have hit it a mile,” Terry later said. “Instead, he was overanxious and popped out.” Now, leading off the bottom of the ninth, came Mazeroski, who had hit only two home runs at Forbes Field since July.

Terry’s first pitch was high – too high to hit. “Get the ball down,” his catcher, Johnny Blanchard, pleaded from halfway to the mound. Terry then threw his fateful slider, and Mazeroski swung.

Terry had only to see the back of his left fielder, Yogi Berra, to know he was in trouble. “I didn’t think it was gone, but it was a dry fall day, and the ball kept carrying and carrying,” he recalled. “I didn’t have it. If Maz hadn’t hit it, someone else probably would have.”

Mazeroski rounded the bases, swinging his arms in joy, mobbed by players and fans, in what became baseball's most famous home run trot. Meanwhile, as The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette put it: “Ralph Terry walked slowly off the field, head down. There would be no champagne for Ralph Terry. The New York Yankees were dead, buried by a high fastball.”

That it actually was a slider didn’t much matter. “I don’t know what the pitch was,” Terry said in the dressing room. “All I know is, it was the wrong one.” Terry’s manager, Casey Stengel, defended him, even though the gopher ball effectively cost Stengel his job.

|

| Terry, center, with his fellow Yankees Mickey Mantle, left, and Roger Maris in 1960. |

Terry rebounded the next year, going 16-3 despite missing six weeks with a sore shoulder. But his postseason woes continued: Cincinnati’s only win against the Yankees in the 1961 World Series came off him.

For the pennant-winning Yankees of 1962, Terry went 23-12, the most wins for a Yankee right-hander since 1928. But Jack Sanford of the Giants bested him with a three-hit shutout in the second game of that year’s Series, bringing Terry’s postseason record to 0-4. Only in the fifth game did he break his streak, beating the Giants and Sanford 5-3. And after a couple of rainouts, he was well rested for another Game 7, on Oct. 16, 1962.

Candlestick Park’s famous winds were blowing in, and for Terry, who’d given up 40 home runs that year – still a team record – it was a blessing. Terry mowed down the first 17 Giants he faced until Sanford collected a single. But the Yankees led 1-0 as the Giants batted in the bottom of the ninth.

Matty Alou led off with a bunt single. Terry struck out both Alou’s brother Felipe and Chuck Hiller, but then faced three future Hall of Famers. The first, Willie Mays, doubled to right; only Roger Maris’s quick relay kept Alou at third. Then came McCovey, and out came the Yankees manager, Ralph Houk.

Several pitchers, including Whitey Ford, had been warming up, but Houk stuck with Terry, leaving it to him, his starter, whether to walk the left-handed McCovey and, playing the percentages, pitch to the right-handed Orlando Cepeda instead.

McCovey had already homered off Terry in the Series and tripled earlier in the game, but Terry opted to pitch to him nevertheless. He’d learned his number, he thought – high and tight – and would work his spots. With a National League umpire behind the plate in a National League park, he knew he’d get no close calls, but he’d at least have a shot at getting him out. And he felt that Cepeda, hitless that day, was due. Terry feared that his second baseman, Richardson, was shading McCovey too close to first, but he said nothing.

McCovey fouled off Terry’s first pitch, a curveball low and away, to right. Then came a fastball. It was lower than Terry had wanted, dangerously resembling the pitch Mazeroski had hit, but inside. McCovey hit a screaming line drive. But it went right to Richardson, and sank rather than sailed. The game, the Series, and Terry's curse, were over.

Ralph Terry was born on Jan. 9, 1936, by his account in the one-room log cabin where he lived with his parents and an older brother on his grandfather’s farmland, halfway between Chelsea and Big Cabin, Oklahoma.

In high school he shut out a team of barnstorming big leaguers, striking out Gene Stephens of the Red Sox three times. Fifteen clubs chased him, but the Yankee scout Tom Greenwade, offering more money than he had promised Mickey Mantle, won out after a tug of war with the St. Louis Cardinals that Ford Frick, then the commissioner of baseball, was left to decide. In spring training 1954, Stengel called Terry the finest pitching prospect he’d ever seen.

The Yankees called him up in August 1956 but traded him, along with Billy Martin, to Kansas City in June 1957. New York reacquired Terry in May 1959, and he began slowly for them.

|

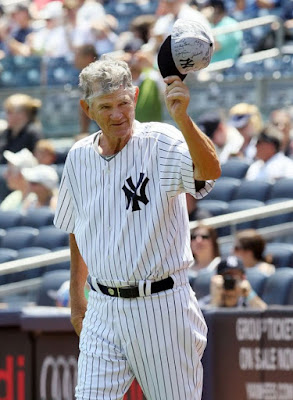

| Terry acknowledged the crowd at Old-Timers’ Day at Yankee Stadium in 2012. |

In 1963 – in the wake of his Game 7 heroics in San Francisco the year before, when he was named the Series’ Most Valuable Player – Terry won another 17 games. But, hampered by injuries, he sank to 6-11 in 1964. After the season, the Yankees traded him to Cleveland. He went on to play for the Kansas City A’s and the Mets, who released him in 1967. He later became a golf professional and worked in oil and gas exploration.

He finished his career with 107 wins, 99 losses and an earned run average of 3.62.

After McCovey’s decisive line-drive out in San Francisco, the specter that had stalked Terry, including abusive letters and heckling from the stands, was suddenly, miraculously lifted.

“Hey, Ralph, now you can forget that ninth inning in Pittsburgh,” Joe DiMaggio shouted that day across the raucous Yankee clubhouse. “That one is washed away now.” Mantle looked toward Terry and said, “That’s got to be the happiest son of a gun in the world right there.”

Terry himself sounded a bit like Lou Gehrig. “I’m probably the luckiest man in the country today,” he said. “If the ball goes a foot or two higher or to one side, I’m the loser.”

Twice over, in fact.

🛐 Today’s close is from Praying with the Psalms, by Eugene H. Peterson.

“Many are the afflictions of the righteous, but the Lord rescues them from them all” (Psalm 34:19).

“Many are the afflictions,” but more are the deliverances. Suffering is no sign that God has abandoned us: adversity is no evidence of condemnation. The love of God and his salvation are proof against every affliction.

Prayer: “O love that wilt not let me go, I rest my weary soul in Thee; I give Thee back the life I owe, that in Thine ocean depths its flow may richer, fuller be” (George Matheson, “O Love That Wilt Not Let Me Go”). Amen.

-30-

No comments:

Post a Comment